Before Europeans came to North America, corn, beans and squash, as well as tomatoes, Irish potatoes, chili peppers, yams, peanuts and pumpkins were the main crops in this region. Spanish colonists brought wheat, oats, barley, onions, peas, watermelons, and domesticated animals to the United States and Texas in particular. At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, new technologies imported from Europe, Asia and Africa began to be implemented in the state’s agriculture. Read more about the agricultural development in Texas at houstoname.

From gathering to animal husbandry

Advanced agriculture developed primarily among the Caddo Indians in the east and the Pueblo cultures in the west, while most of Texas was inhabited by nomadic groups of hunters and gatherers. The first ones mainly cultivated corn, beans and squash. When preparing fields for sowing, they used the method of burning. The land was tilled with wooden hoes, stones, and sharpened sticks. Pueblo peoples also grew cotton for fiber and practiced irrigation.

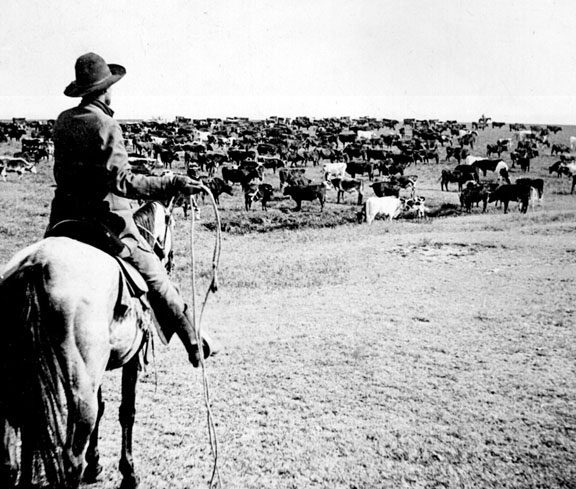

After the colonization of Texas by the Spaniards, animal husbandry began to develop here. Cattle, sheep, goats and pigs were usually bred there. Agriculture was mostly limited to small garden plots near settlements. Over the next century, in Texas, which was dominated by the Comanche, Apache and other nomadic tribes, ranching and farming did not progress significantly.

Cotton and livestock exporter

After gaining independence from Spain in 1821, Mexico, which included Texas at the time, encouraged settlers to come to its vast provinces north of the Rio Grande River. Newcomers received a land plot for cattle grazing and labor. Then, Americans introduced slavery on cotton plantations. The influx of Anglo-Americans led to the Texas Revolution and in March 1836, Texas became independent from Mexico.

Between 1836 and the Civil War, the plantation system in the state expanded significantly. The number of small family farms and large cattle herds increased. Cotton production grew from 58,000 bales in 1850 to over 431,000 bales in 1860. During the same period, the number of slaves increased from 58,161 to 182,566 individuals. Cotton and cattle were exported in the first place.

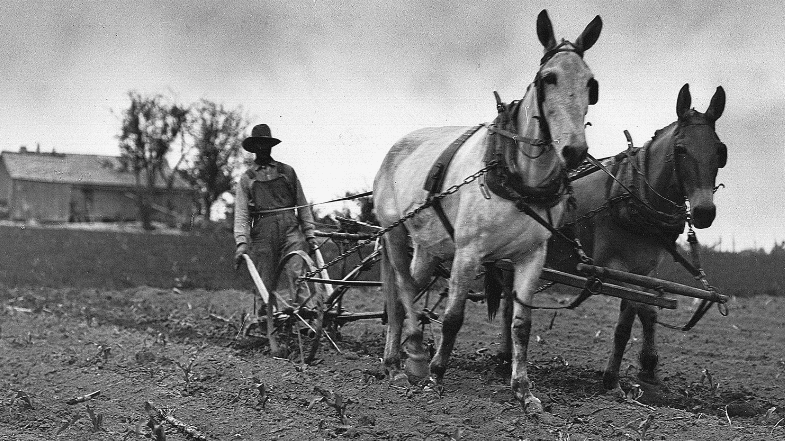

It was common to use oxen and, sometimes, horses or mules (a crossbreed between a horse and a donkey) for plowing on farms and plantations. Plows were either made on-site or imported through New Orleans and Galveston if money were available.

After the Civil War, the sharecropping system became popular. Landowners entered into contracts with tenant farmers to cultivate a small plot of land. Tenants grew crops and shared revenue from sales with landowners in exchange for providing land, tools and housing.

By 1900, Texas already had 350,000 farms. Cattle breeding and cotton production were the dominant sectors of farming. However, wheat, rice, sorghum, hay and dairy products were also popular.

Mechanization and modernization

In 1876, the Texas Agricultural and Mechanical College (later Texas A&M University) was opened near the city of Bryan. The college sponsored agricultural institutes throughout the state and founded the Texas Farmers’ Congress. Scientific research contributed to the improvement of cultivation technologies, the development of plant varieties and agricultural mechanization. As a result, it led to rich harvests and extension of acreage.

After the Civil War, prices went down while credit and transportation costs increased, accelerating the formation of cooperatives among farmers. In 1872, the Farmers’ Alliance appeared in Lampasas County. In 1887, by way of the merger of this Alliance with the Farmers’ Union of Louisiana, the National Farmers’ Alliance and Industrial Union of America was created.

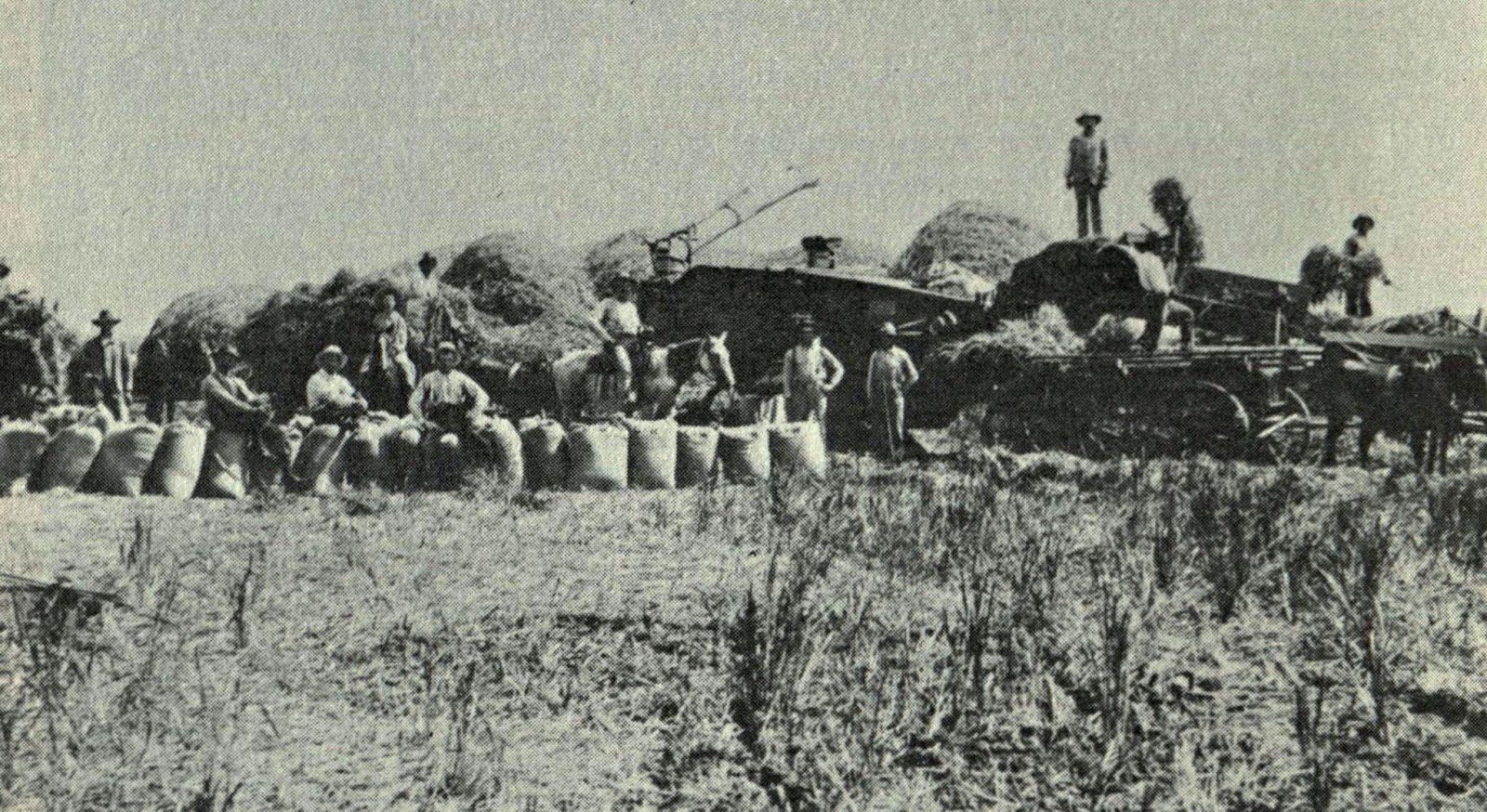

Wheat was the main commodity for export until 1900. In 1908, citrus production was launched in the state. In addition, onions, cabbage, lettuce, carrots, beets and spinach were grown here as well. Rapid urbanization in the United States in the 1920s and the outbreak of World War I increased demand for farm produce.

When Texas scientists adapted cotton varieties to the plain terrain, they began using tractors, one way disc ploughs and combine harvesters for sowing and growing winter wheat.

The economic environment for Texas farmers was improved due to the demand for agricultural products during World War II. Thus, the foundation for the modernization of the state’s agricultural system was laid. An important step in the transformation of Texas farm life was achieved through increased mechanization. Although steam and gasoline tractors appeared in the late 19th and early 20th centuries before World War I, mules and horses remained the main power source until the 1940s.

After the war, farmers started applying high-speed plows, circular and tandem harrows, grain drills and other tools. Harvesting technology was also innovated. Machines for gathering hay, spinach, potatoes, beans, sugar beets, nuts and peanuts significantly reduced the need for manual labor.

In the 1940s, the sale of cotton harvesters made a breakthrough in production. Around the same time, engineers solved technical difficulties related to reaping equipment, while scientists bred new cotton varieties, herbicides and defoliants that wiped out a significant portion of weeds. By the late 1960s, cotton manufacturing was almost entirely mechanized. By the 1990s, Texas cotton was gathered and processed by machines.

The cultivation of sorghum plants prompted the development of livestock fattening. In the early 1970s, over three million heads were sold annually. Texas became a leader in the production of fat cattle in the country. Therefore, corn, as an important commodity in the state, was in demand again.

A number of challenges

After the technological, scientific, economic and political factors converged, large commercial farms and ranches took over in the agricultural system of Texas. Because of the substantial costs of chemicals and improved seed varieties, many farmers quit their profession when they discovered that expenses were beyond their reach. From 1945 to 1990, the number of farms decreased from 1.52 million to approximately 245,000. The lifestyle of Texas farming families also changed after World War II. When rural cooperatives were provided with electricity, farmers began to enjoy the same amenities as urban residents.

The income of farmers was also affected by environmental and climatic problems. Crops suffered from drought, diseases, and insects. Ranchers felt hopeless when their yields were destroyed by hail or frost. In addition, the sharp rise in natural gas prices in the 1970s adversely impacted the agrobusiness. That is why irrigated cotton producers had to cut their acreage.

Several measures have been taken to improve the situation. The state created districts where water was kept. Also, minimum tillage techniques were introduced and more efficient equipment was installed, such as underground irrigation sprinklers.

Despite all these challenges, Texas agriculture remained a vital industry both in the state and the country at the end of the 20th century. Until the 1990s, the income from crop and livestock production continued to grow. Texas became one of the leading farming states.