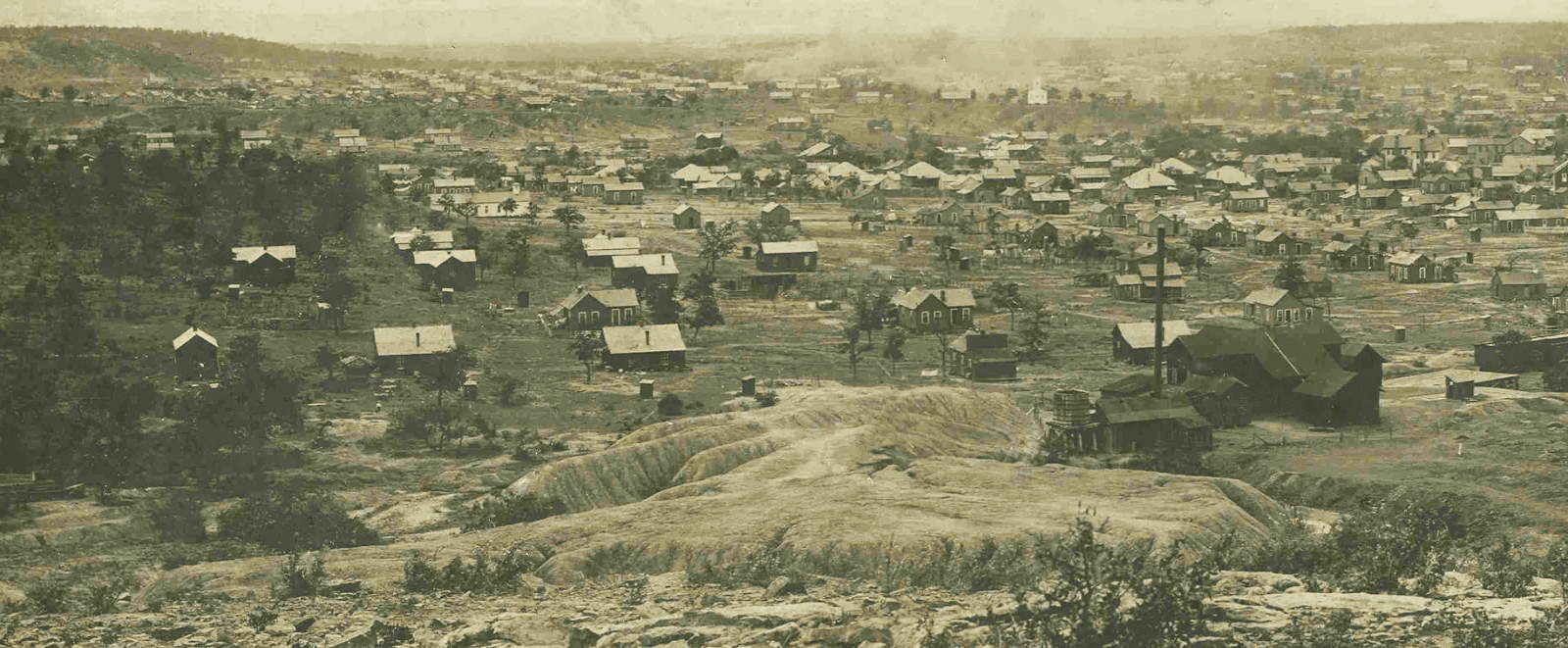

Texas ranks first in the United States in the number of ghost towns, that is abandoned settlements. However, few were as large as the corporate town of Thurber (west of Fort Worth), which was home to 10,000 people. From 1886, when William Whipple Johnson and Harvey Johnson dug a mine with bituminous coal, Thurber became known for its booming coal, brick and oil industries. The city remained famous until 1940 when it became deserted. Read more about one of the largest producers in Texas at that time at houstoname.

The first restricted trading town

As mentioned above, bituminous coal mining began in Thurber in 1886 under the leadership of the Johnson brothers. Two years later, Scottish cattle farmer Robert D. Hunter purchased the business after realizing a lucrative opportunity in this mineral. The Texas and Pacific Railway, which ran west of Fort Worth, required coal to power its trains.

Acquiring the coal fields from the Johnson brothers, Hunter founded the Texas and Pacific Coal Company. It had to extract bituminous coal and sell it to the railway and other customers. Bituminous coal is a type of coal with high volatile matter, carbon and oxygen content; it has high calorific value and sulfur impurities.

At that time, there were already many trade unions in the United States. That is why the Thurber’s mines attracted leaders of such organizations. Before the Johnson brothers sold off their property in 1888, the Knights of Labor started a strike. To control the miners, the Texas and Pacific Coal Company formed a separate community for the workers.

The town boasted churches, schools, parks, strong sports teams, an ice factory, a power plant, a 650-seat opera theater, a 200-room hotel and the only public library in Erath County. This town more resembled Pennsylvania’s Pittsburgh or Cleveland in Ohio, rather than big Texas cities.

The company hired miners on its own terms, except for union activists. As the coal pits were somewhat isolated, workers were recruited from afar, primarily from Italy, Poland, Great Britain and Ireland.

In 1899, a smart and educated engineer from Virginia, William Knox Gordon, became the vice president and manager of the Texas and Pacific Coal Company, which actually owned the town of Thurber. Gordon and the new company president, Edgar L. Marston from New York, abandoned Hunter’s non unionism policy. In 1903, the local mining enterprises merged into one union. Thurber became the first completely closed trading town in the United States.

At one time, the town of Thurber could have had the highest number of trade unions in America. Its residents either worked for the Texas and Pacific Coal Company or were carpenters, butchers, clerks or bartenders, in other words, representatives of unionized professions.

Brick production

Realizing that the town has inexhaustible shale reserves, the workers of the company sent its assay to brick manufacturers in St. Louis, Missouri in 1897.

When they got approval from the experts, the Green and Hunter Brick Company was founded in Thurber. The town produced 80,000 bricks per day, primarily for road pavement. Thurber’s paving bricks were used in Fort Worth, Dallas, Houston, Galveston, Beaumont and other southern American cities. For example, the Dallas Opera, the Texas and Pacific Railway station and the First National Bank in Fort Worth were built from this brick.

Initially, the workers dug slate from a hill adjacent to the kilns. In 1903, the company laid a rail track from the brickworks to a place north of the kilns, which had a rich shale deposit. The bricks had been transported by electric locomotives until gasoline engines began to be used in the 1920s. Shortly after World War I, the construction brick plant burned down, and the company focused on producing paving bricks.

Transition to oil, strikes and decline

In the first quarter of the 20th century, railroads switched from coal to oil to power steam locomotives. Therefore, the market for bituminous coal mined in Thurber experienced a decline. The economic changes spelled the end for the industrial enterprises in this town.

Understanding that coal could not sustain competition with other types of fuel, especially oil, William Knox Gordon began exploring this inflammable liquid in the area around Thurber. As early as 1915, he discovered an oil well west of the city of Strawn, but it did not yield the desired results. Later, Gordon received a letter from New York stating that the company needed to cut the cost of coal mining and increase oil production.

Making sure that there were reservoirs of oil in West Texas, Gordon used his knowledge of geology to continue the search. Experienced geologists could not find new wells, but persistent Gordon did not give up. Subsequently, the first natural gas well was drilled in the Texas city of Ranger. At that time, it had no market value but indicated the presence of oil. In 1917, a second well was drilled in Ranger, which turned out to be a real oil gusher. A year later, the Texas and Pacific Coal Company was rebranded to the Texas Pacific Coal and Oil Company. The company relocated its headquarters from New York to Thurber in 1923 to be closer to its physical operations.

After the company was unable to provide higher wages, trade union workers staged a strike in 1921. The company continued to extract coal in limited quantities until it finally shut down the mines in 1926. In addition, the state began using oil-borne asphalt as a much cheaper alternative to brick for paving. As a result, the brick market also declined. In 1929, the United States faced the Great Depression. A year later, brick kilns were closed down.

The income from oil was not enough to save Thurber. In 1933, the Texas Pacific Coal and Oil Company moved its offices to Fort Worth and closed its thrift shops two years later. In 1936, all residential buildings in the city were closed. Some houses were sold and others were demolished.

Notable landmarks

The town of Thurber is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The ghost town’s famous sights include the cemetery with over a thousand graves, the restored St. Barbara’s Catholic Church and the reconstructed and furnished miner’s house.

From Interstate 20, you can spot the iconic Smokestack of Thurber. There is also the W. K. Gordon Center for Industrial History, a historical museum and the Smokestack Restaurant, as well as New York Hill restaurant, built on the site of the former Episcopal church on top of New York Hill. Steam Shovel Mountain, where red bricks were once mined, can be seen there too.

The exhibitions at the Gordon Center are dedicated to the life, work and entertainment in the town of Thurber. At the same time, the center engaged in researching other aspects of the industrial industry in Texas.

The museum has things to offer to people of different age groups. Younger visitors will be interested in bright events of life in Thurber, while detailed stories about the history of the city will appeal to older guests. There is also a somber sculpture of a miner chopping off bituminous coal.